Where is Jura Mountains, France/Switzerland? – Jura Mountains, France/Switzerland Map – Jura Mountains, France/Switzerland Map Download Free

Jura Mountains, France/Switzerland

Jurassic

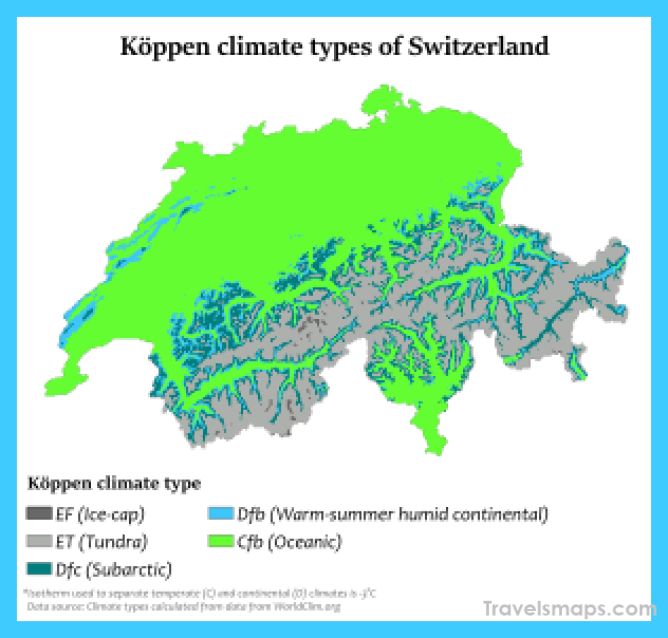

Now for a walk in the mountains – the Jura Mountains to be precise, straddling the border between Switzerland and France. The name Jura derives from an ancient Celtic word meaning ‘forest’, and these tree-covered peaks mark the more verdant western end of the Alps. What brings us here is a term from palaeontology that has been shaped and reshaped over hundreds of millions of years.

Where is Jura Mountains, France/Switzerland? – Jura Mountains, France/Switzerland Map – Jura Mountains, France/Switzerland Map Download Free Photo Gallery

There can’t be many terms from the geological timeline that have fallen into mainstream use, but Jurassic is certainly one – and you can thank the author Michael Crichton and film director Steven Spielberg for that. Crichton’s 1990 science fiction novel Jurassic Park and its resultant film franchise, in which dinosaurs are reborn using DNA extracted from fossilised mosquitoes, have helped lift a term from fairly obscure geological contexts into practically every English speaker’s vocabulary. Certainly, the same can’t be said for the word Jurassic’s geological contemporaries: Ordovician Park doesn’t have quite the same ring to it (and, admittedly, a theme park filled with the kinds of primitive molluscs and jawless fish that developed during the Ordovician Period wouldn’t be quite as menacing as Jurassic Park’s dinosaurs). But if we can thank the success of Jurassic Park for the word’s familiarity today, who can we thank for the word Jurassic itself?

This story begins with the terrifically named Abraham Gottlob Werner, born in Silesia (now in modern-day Poland) in 1749. A mining inspector by trade, in the late 1700s Werner became interested in the differences between the geology of one region and another, and one strata of rocks compared to the others around it.

Quite correctly, he theorised that these different rock formations must correspond to different periods in the history of the Earth. Less accurate was his follow-up theory: that the Earth began life covered in a single vast mineral-rich ocean. This enormous primordial sea, Werner believed, steadily receded over thousands of years while depositing the different rocks that now make up our landscape at different periods in time.

This water-based theory of the Earth’s geology fittingly became known as Neptunism, after the Roman god of the sea. But eventually it was proved to be misguided, and Neptunism was superseded by better-informed theories in the nineteenth century. Werner’s notion that different rock formations corresponded to different geological time periods nevertheless endured – and that brings us to the next character in our story: the Prussian geographer Alexander von Humboldt, born in Berlin in 1769.

Humboldt’s contribution to science is so gargantuan that labelling him merely a ‘geographer’ does not do him justice. Among the countless disciplines his work influenced are geology, botany, zoology, mineralogy, meteorology, geomagnetism, astronomy and navigation, besides which he carved out a career as an explorer, travelling extensively around the Americas on a grand five-year voyage from 1799 to 1804. As a result, everything from a species of South American penguin to a Peruvian sea current have been named in his honour – but it’s another contribution to our dictionary that concerns us now.

In 1795, shortly before his American expedition, Humboldt found himself on a tour of the French-Swiss mountains. While out walking one day, he began to contemplate the geology of the region around him and attempted to ally what he saw with Werner’s theories. Werner had classified the limestone mountains of Central Europe as Muschelkalk – literally ‘mussel chalk’, a type of seashell-bearing limestone deposited relatively late in Earth’s timeline. Humboldt, however, thought otherwise.

‘I became convinced,’ he later wrote, ‘that the Jura limestone was a distinct formation’, isolated between a distinct layer of older gypsum above it, and newer sandstone below. This ‘Jurassic’ limestone did not fit with Werner’s theory and so, Humboldt believed, must have been formed at a different period of time.

Later geologists picked up on Humboldt’s ideas, and began to identify ever more subtle differences between Werner’s original classifications. Eventually, an entirely new classification of rock was established – along with an entirely new stage of geological time, with its own fossil record and unique flora and fauna. Thanks to Humboldt’s Alpine holiday, it took a name honouring the Jura mountains: the Jurassic period, as we now know it, had finally arrived.