Kahlenbergerdorf, Austria

Kahlenbergerdorf, a picturesque district of the Austrian capital Vienna, is believed to be the origin of the little-used word calembour, meaning ‘pun’ or ‘play on words’, borrowed into English from French in the early nineteenth century. If you think those two words don’t look anything alike, you’d be right. They don’t. So how did one inspire the other?

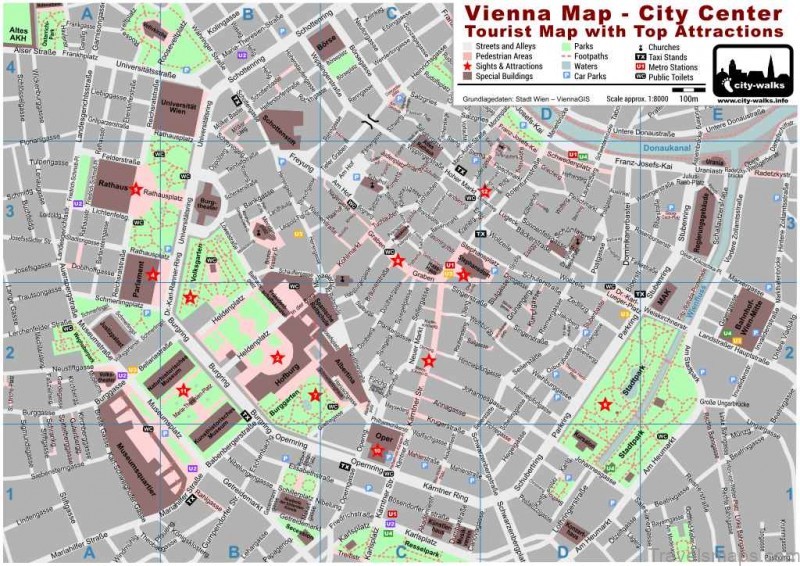

Where is Kahlenbergerdorf, Austria? – Kahlenbergerdorf, Austria Map – Kahlenbergerdorf, Austria Map Download Free Photo Gallery

One popular explanation is that the missing link here is an otherwise unnamed Count of Kahlenbergerdorf, who, according to a nineteenth-century Dictionary of Science, Literature and Art, ‘visited Paris in the reign of Louis XV, and was famous for his blunders in the French language’. The French name for Kahlenbergerdorf (or rather, Kalenberg as it was known at the time) was Calemberg, and with a little bit of etymological jiggerypokery, it was this tongue-twisting Count of Calemberg whose name eventually morphed into calembour.

It’s a neat story, certainly, but alas there’s little evidence to back it up. Instead, the more likely explanation here is a much more convoluted tale involving a fourteenth-century Austrian clergyman, a stock character from German theatrical farces, and yet more etymological jiggery-pokery.

The Austrian clergyman in question was one Gundacker von Thernberg, who served as the parish priest of Kahlenbergerdorf from 1339 to 1355. Very little is known about Thernberg’s life, but given how he was to become immortalised in the years after his death, we can presume that he was a fairly witty and wily character whose deeds (and maybe misdeeds) earned him quite a reputation. How do we know all that? Well, in the late 1400s, long after Thernberg’s death, a Viennese writer named Philipp Frankfurter compiled an anthology of comic tales called Pfarrer vom Kalenberg (1473), or the ‘Priest of Kahlenberg’. Frankfurter’s collection was reportedly based on well-known local anecdotes about a knavish parish priest in Kahlenbergerdorf, who would play practical jokes both on his parishioners and on the members of the nearby Duke of Vienna’s court:

On one occasion, [the priest] had purchased a quantity of wine, and finding it too bad for his own drinking, he announced that he intended to fly from the steeple of his church across the Danube. A number of peasants collected to witness the miracle. The priest kept them waiting a long while. The day was very hot, the peasants wanted something to drink, and the rector’s sour wine went off [i.e. sold] at a famous price. When it was all consumed, the priest appeared, and asked the people whether they had ever seen a man fly? As a universal ‘No!’ was answered, he continued, ‘Well, then, you shall not see me; it is a sinful thing to desire such an extraordinary novelty. Go home -1 give you my blessing!’ The peasants went away, some laughing, some cursing; but the priest was enabled to buy better wine.

In another story, the priest introduces himself to the local duke, who offers him a gift in return for his loyalty. Oddly, the priest requests a hundred lashes, and gladly accepts fifty of them before pointing out that the duke’s gatekeeper had admitted him into the court only if he promised to give him half of whatever gift the duke bestowed on him.

To the amusement of the duke – and presumably the priest – the gatekeeper was called for, and promptly awarded his fifty lashes.

Frankfurter’s anthology of stories soon proved hugely popular throughout Europe, and before long the prankster priest of Kahlenberg had become a stock character in German and Austrian literature and comic theatre. A vast catalogue of stories associated with him had soon emerged, and other collections of comic tales demonstrating both the priest’s craftiness and his cruel sense of humour began to be published elsewhere.

The name Kahlenberg ultimately became a nickname for a wisecracking anecdotist or practical joker, and it remained in use in this sense long after the tales that had inspired it fell out of fashion.

But with these tales now drifting into obscurity and without their context to support it, the word Kahlenberg began to change. In French, it became confused with the word bourde, meaning ‘blunder’ or ‘stumble’, and in the late eighteenth century a new word entered the language: calembour. Combining a word for a wise-cracking comedian with one for someone who literally ‘stumbles’ or ‘blunders’ their words together, calembour came to be used for a pun or an instance of wordplay, and it was in that sense the word drifted into use in English in the early 1800s. It only remotely caught on and calembour has remained something of a linguistic curio ever since.

Frankfurter did not name the priest who had inspired the stories in his collection, but later writers did. Before long, Gundacker von Thernberg had soon been identified as Kahlenberg’s knavish, joke-playing priest.