Magenta, Italy

We now enter Italy, a country in which we’re spoilt for etymological choice. Among the countless words and phrases we owe to the Italian map are words as familiar as jeans, which take their name from Genoa (where a thick corduroy-like fabric known as Gene fustian was once made), and cantaloupe melons, which were introduced to Europe from Asia but take their name from Cantalupo, a papal estate outside Rome where they were once grown.

Where is Magenta, Italy? – Magenta, Italy Map – Magenta, Italy Map Download Free Photo Gallery

Bergamot takes its name from Bergamo in Lombardy, while leghorn chickens namecheck the Tuscan port of Livorno. Tarantulas are named after the city of Taranto in southern Italy, where a huge species of wolf spider first became known by that name in the sixteenth century. And the Rubicon you proverbially cross when you go too far to turn back is the name of a shallow river that empties into the Adriatic just north of Rimini. Famously, as the river once marked the boundary between Italy proper, Italia, and the Roman province of Cisalpine Gaul, when Julius Caesar ‘crossed the Rubicon’ on his way to Rome in 49 bce, he effectively declared war on the Italian king, Pompey – with no going back.

At the more obscure end of the scale, sybarites are lovers of luxury, or hedonistic devotees of pleasure or indulgence, whose name derives from the Ancient Greek colony of Sybaris that once stood on Italy’s south coast. Faience, a term for glazed earthenware or ceramics, originally referred to a specific type of tin-glazed pottery manufactured in the city of Faenza in Ravenna. And the seldom used but eminently useful adjective fescennine, meaning ‘obscene’ or ‘scurrilous’, derives from the Ancient Roman city of Fescennia, in modern-day Lazio, whose citizens were apparently known for their bawdy drinking songs and indecent verses.

Italy is also responsible for the names of three colours or pigments: sienna, umber and magenta.

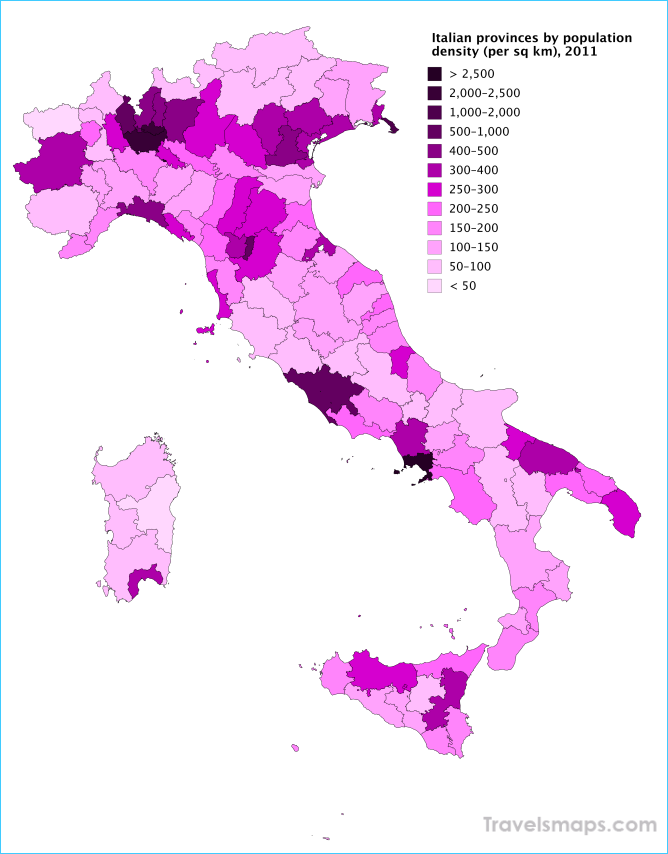

Sienna, or terra-sienna, is an earthy reddish-brown colour manufactured originally from the iron-rich clay found around the city of Siena in Tuscany. The name of another earthy orange colour, umber, is probably a jumble of the Italian for ‘shadow’, ombra, and the landlocked province of Umbria in central Italy. And magenta – one of the four basic shades of colour printing, alongside yellow, black and cyan – takes its name from the town of Magenta just outside Milan, in Lombardy, in the far north of Italy.

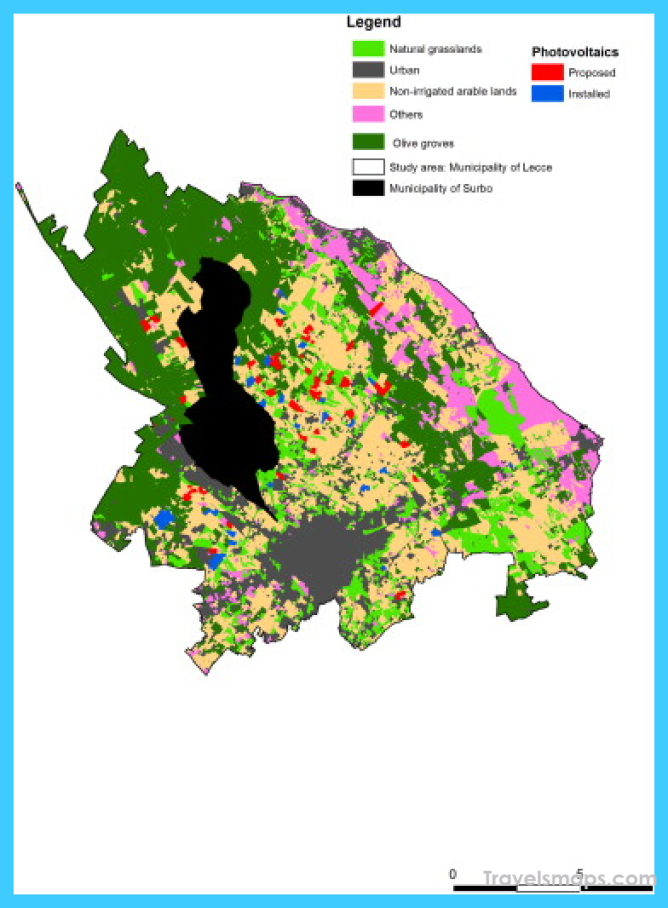

It was here, on 4 June 1859, that a bloody battle was fought by the allied forces of the French empire and the Sardinian Army against the considerably more sizeable Austrian Army. Under Napoleon III, the French secured a narrow but decisive victory at Magenta. By crossing a nearby river they outflanked the Austrian troops, forcing them to retreat into the surrounding countryside where the French pressed home their advantage. The sweltering hot weather made fighting difficult, while the terrain – a mixture of orchards, streams and irrigation canals – made any of the large-scale military manoeuvres the Austrians excelled at all but impossible. Hand-to-hand fighting with swords and bayonets ultimately dominated the battle, and as the French stormed the nearby town of Magenta, steadily emptying the heavily fortified buildings of their Austrian sharpshooters, they quickly secured their victory.

But what connects this sweltering hand-to-hand battle to the purplish dye we know as magenta today? One explanation claims that the colour was a reference to the bloodied uniforms of the French and Austrian troops – but magenta is more of a pinkish-purple shade than it is blood-red, which suggests this might be little more than linguistic folklore. Another theory claims that the French side was vastly fleshed out with hundreds of zouaves, light infantrymen of Algerian or North African origin, who were known for wearing a distinctive and often brilliantly coloured uniform of headbands, short open jackets, and bright, crimson-red billowing trousers. But again, crimson isn’t magenta and the zouaves were involved in a great many more battles than this one. Instead, as is often the case in etymological conundrums, it seems the most likely theory is also the most straightforward.

The Battle of Magenta came partway through what would eventually become known as the Franco-Austrian War. At the time, much of northern Italy was under Austrian control, but the French victory at Magenta had demonstrated that even this great empire could still be beaten and overthrown. Before long, many towns and cities across the north of Italy had risen up and begun rebelling against Austrian rule; the battle had marked a turning point in the war, and after it the fight to reunify Italy greatly picked up pace.

As it happens, some two hundred and fifty miles west in Lyon, another turning point – a somewhat less momentous one – had been reached. A French chemist named Fran^ois-Emmanuel Verguin had developed a new bright purple aniline dye, more vivid and potent than any similar dye had been before. Verguin originally named his invention fuchsine, after the purplish flowers of the fuchsia shrub that it resembled, but as the dye caught on across France it eventually came to be associated with the name of the staggering French victory that was soon the talk of the country.

Whether Verguin was happy with the name change or not is unknown. Whether he was or not, the name soon stuck, and magenta joined the long list of Italian place names that have since become immortalised in the English dictionary.

Cantalupo, incidentally, means ‘place of the singing wolf’. No one is entirely sure why, but it’s possible the name refers to the fact that the wolves howling in the hills around Rome could be clearly heard there.

Whether the English chemists Chambers Nicolson and George Maule, whom Verguin beat to the discovery of magenta by just a matter of months, were happy with the situation is an easier question to answer.