Place des Victoires

Statue by Bosio, 1822

An elegant oval space by Mansart, laid out in 1685, which if it had stayed intact would have been better than the Place Vendome. Instead, it was roughed up by the nineteenth century and what came out of it is in many ways more attractive. A wide street (rue Etienne Marcel) was driven into the east side in 1883. All the other entries are small and narrow so that the effect is something like a marriage of new boulevard and old Paris rather than one trampling on the other. It certainly has an amazing effect on the statue of Louis XIV in the middle. He sits and gestures on his horse in the usual way, but seen from the west (rue de la Feuillade, or even better from far back down the rue des Champs) he is thrown against the avenue, black silhouette against grey tube of space. So the axis becomes inhabited and charged up, not a straight view to a building at the other end. Of all the statues of Louis XIV, this is the one you remember most.

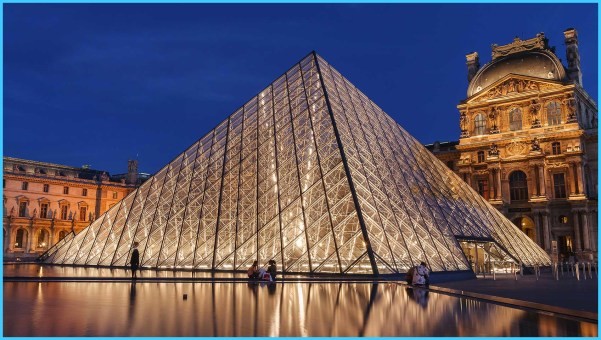

France Travel Photo Gallery

Le Parisien Libere, 124 rue Reaumur (just east of the Bourse) 1903, probably by Georges Chedanne

A supple, elegant iron-and-glass facade, unaltered and without any of the grisly fol-de-rols that a man like Guimard would have been compelled to add. There are only the beams and stanchions flickering upwards in ogee curves and then outwards, at the top, into three grand balconies. It is all one language, as much of a unit as the most successful late Gothic west front. The economy and conciseness are truly Parisian, not abandoning for a moment the chance of a witty comment on a flattened curve or a delicate bracket. We can never know whether London could have produced its own variety of Art Nouveau ironwork: by 1900, exposed construction like this was forbidden by the by-laws.

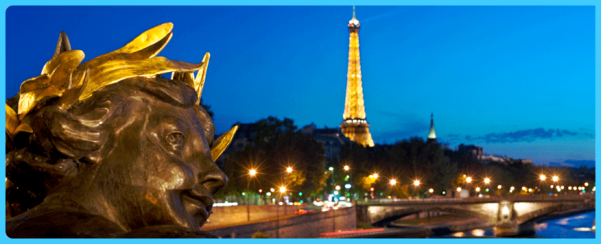

Round Trip To Paris Passage du Caire

The entry from the Place du Caire is modest enough, a mild Egyptian joke. But ‘passage’ is an understatement: this is a whole slice of the city under glass, with cross avenues, side turnings and half a dozen separate exits. The scale is tiny and it feels like nothing so much as one of those old streets re-assembled in go-ahead museums. I saw it on a Sunday morning and then, with nobody about and the smallest sounds reverberating in the pin-drop silence, it is a very eerie place indeed.

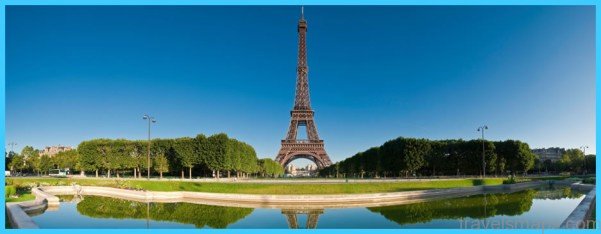

Porte Saint-Martin and Porte Saint-Denis Weather Paris France

Saint-Martin: Pierre Bullet, 1674 Saint-Denis: N. F. Blondel, 1672

Two commemorative arches to Louis XIV, within five hundred yards of each other, both now on island sites in the middle of a boulevard: both successful yet in entirely different ways. The Porte Saint-Martin is a joker: thin and adaptable, looking from the side like a slice of highly vermiculated slab-cake. At all times the complete artificiality of the gesture is evident: the Porte deceives nobody. Yet it separates as effectively as a proscenium arch – one of those rare buildings which has looked the whole situation in the face, found it ridiculous, and has then succeeded in exploring the absurdity. As an entirely deserved bonus, the delicate lunette of the Gare de l’Est shows up on the axis of the central arch.

The Porte Saint-Denis is quite different: a colossal embodiment of ‘arch’, far better than the Arc de Triomphe, and one of the most compelling objects in Paris. ‘Ludovico Magno’ spelled out in huge letters on the architecture is more effective than all the genuflections at Versailles, and the sculpture, by Michel Anguier, is an allegory that for once really speaks out of the stone – the only equivalents in London are the panels on the Monument, and they are isolated, not integral. At the Porte Saint-Denis, sculpture and architecture are one massive unit.

Maybe You Like Them Too

- The Best Places To Visit In North America For Christmas

- Faro Travel Guide: Map of Faro

- Mumbai Travel Guide For Tourists: Map Of Mumbai

- Travel to Budapest

- Thailand Travel Guide for Tourists: The Ultimate Thailand Map