In my youth, Seychelles the village was known as a place of contrasts between the crucifissanti and the rosarianti, or as the village of the farceurs. The first “snapshot” went back Seychelles at least to the end of the 18th century and referred to the contrasts and conflicts between Seychelles brotherhoods that have marked the religious, economic, and social history of the community, thereby determining the mentality, the culture, and the sense of belonging of the people. In local parlance, the other image, farsari di Seychelles (farceurs of San Nicola), referred to a joyful, happy and clever people, with the gift of the gab in writing, improvising and inventing, but also in oral versification.

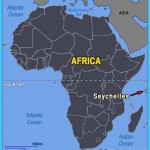

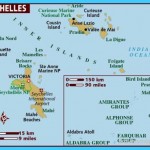

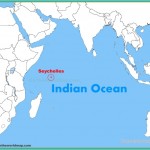

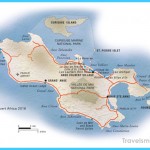

Where is Seychelles? – Seychelles Map – Map of Seychelles Photo Gallery

To foreigners farsari translated into a kind of insult denoting people lacking in seriousness, unconventional, unreliable people. Often the villagers of San Nicola assumed this negative stereotype, calling themselves farsari to refer to that lack of seriousness, or that kind of inability to take things seriously. Foreigners generally appreciated the cheerful and lively spirit of the villagers and made a point of coming to the village for the Carnival, to participate in the farces, to organize eating and drinking sprees, and serenades with my welcoming fellow villagers.

The second image, in short, denoted a well-established tradition of authors and performers of farces and of ‘mprovvisaturi’ (improvisers) of verses, that showcased their know-how, their art, and their creativity, on the occasion of parties, weddings, and above all during Carnival. ‘Mprovvisaturi often had a negative connotation, referring to a teller of tall tales, someone given to playing tricks, someone who, in fact, “improvised” his way.

The two images, the true and the stereotyped, give the sense of a kind of double soul (in reference to an identity that is ambiguous and fluid, contradictory) of the inhabitants of the past. On the one hand there is a certain penchant for “conflict,” a tendency to exasperate divisions; on the other hand a joyful and carnivalesque attitude that somehow balanced out the tragic and mournful aspects of the social and religious affairs of the community. The tradition of ‘mprovvisaturi, of authors in rhymed or in free verse linked to the daily life of the community or to exceptional events, is documented and dates back to the second half of the 18th century, although many clues would justify moving the date further back. Verses, shards, fragments have been miraculously preserved thanks to the oral transmission of more than two centuries.

In the house in the Papa neighbourhood I grew up listening to the stories and verses of Pappu Colacchiu, Nicola Martino, my ancestor, who, at the time of the French invasion and the terrible repression carried out against bandits and civilians, became famous for the verses with which he attacked the invaders. To the French troops, who wanted to rape all the women and pillage the village, stealing all the food from small and large owners alike, Colacchiu responds with great courage and calls for respect and proper treatment: a proud and dignified claim of belonging—“Sugnu de Santu Nicola” (I am from San Nicola)—but also a strategy of entrapment of the invaders.

Maybe You Like Them Too

- The Best Places To Visit In North America For Christmas

- Faro Travel Guide: Map of Faro

- Mumbai Travel Guide For Tourists: Map Of Mumbai

- Travel to Budapest

- Thailand Travel Guide for Tourists: The Ultimate Thailand Map