Saint-Denis: abbey

It is ironic that Saint-Denis has become chained so firmly to Abbe Suger and his invention of Gothic – or at least a shrewd public-relations claim to have invented it. All that remains of his work of c.1140 is the west end, the apse and piers of the ambulatory, and the crypt. It may have been the first design to do certain things, but, with two exceptions, it is not doing them very well. One, distinctly un-Gothic, is the carving on capitals in the crypt; vegetable patterns stylized in a classical way which seems nearer Rome than Reims. The piers are low, so that you can really see them Also in the crypt, there is an evocative excavation of layer after layer of church building from the original Gallo-Roman temple onwards, right up to the concrete roof which now supports the floor of the choir. The other exception is in the ambulatory itself, where you can suddenly feel the excitement which certainly gripped Suger. For the first time, the wall was vanquished, all the parts of the building were speaking together: vault, tabernacles, wide windows in a crinkle-crankle skin filled with sparkling glass.

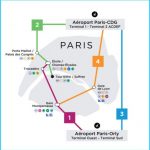

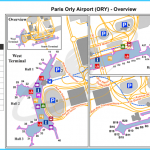

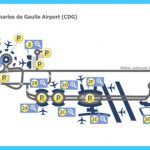

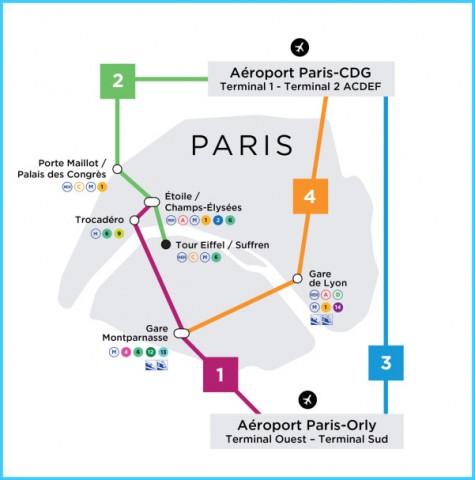

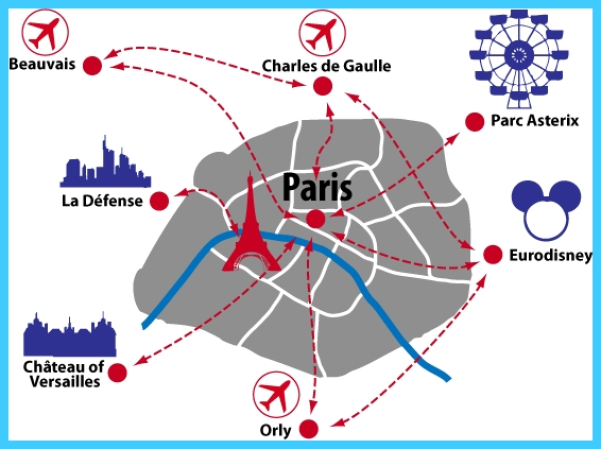

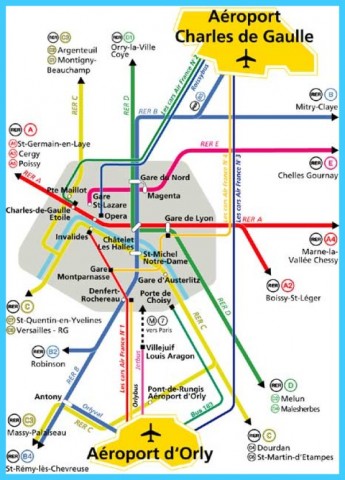

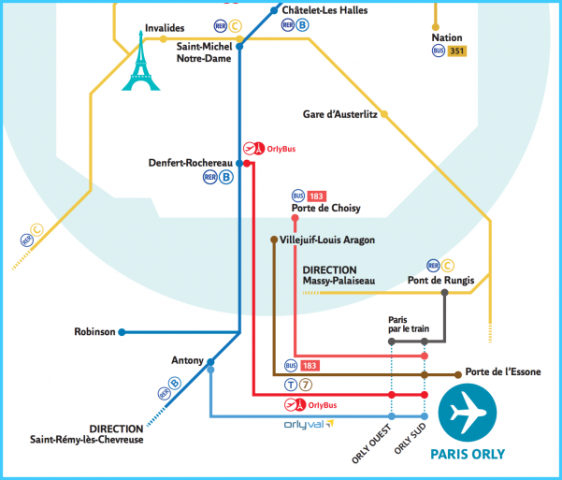

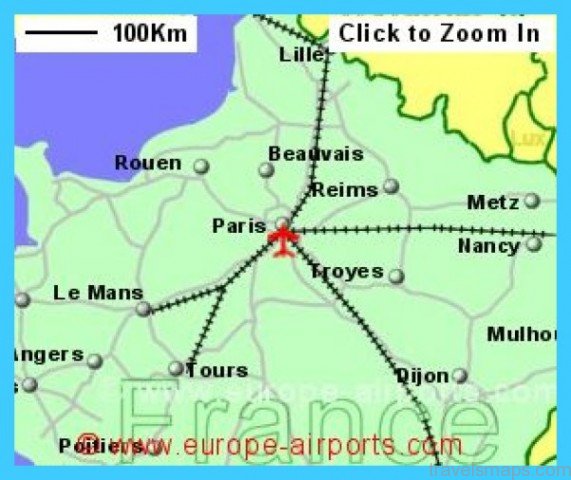

Paris Map Airports Photo Gallery

The rest of Saint-Denis was built by Pierre de Montereau, the designer of the Sainte-Chapelle, from 1247. It is possibly the High Gothic masterpiece – the exact point at which the problems of order and organization were solved, and solved easily and laughingly, almost casually, not striving earnestly after achievement. Because of that, the real achievement is all the greater. The bay-design finally resolved all the grammatical problems inherent in Gothic design so that the structure reads logically. The clerestory windows are divided into four, and the division is carried down into the triforium to make the whole area above the main arcade into one lucid unit – the first time this was ever done. The clerestory is a single wall, the triforium is double with glass outside and tracery inside. The main arcade makes with the aisle walls a much deeper double plane. So the distribution of light is logical too, less shadow and more colour as you look upwards. The proportions are classically harmonious: everything is devoted to making a single, luminous, weightless space that has floated in like a balloon and is barely tied down. It is all created from inside, an expression of a single idea, not constructed from outside, and it is no accident that it feels like the best late Gothic churches in Belgium or Germany: it leapt two hundred years to the final expression of Gothic space. The only drawback was that ordinary architects could not follow, and French architecture marked time for those two hundred years.

The other overwhelming reason for going to Saint-Denis is the monuments; and for a quick visit the situation is not helped by the fact that Saint Louis ordered effigies of all his ancestors back as far as Dagobert – Merovingians in incorruptible thirteenth-century dress. We did the same thing in various places, but never on this overwhelming scale. The eye simply has not time to make distinctions between twenty or thirty superficially similar kings and queens. This does not apply to the Romanesque Virgin and Child by the entrance to the crypt, a worthy partner to Jouy-en-Josas. It came originally from Saint-Martin-des-Champs in Paris.

With the Renaissance it is rather different. At least four monuments make an immediate and distinct impression, all of them sixteenth-century. The three earliest (Francois I, Louis XII, and Henri II) all use the same noble convention of a temple with the bodies stretched out in death inside and kneeling as in life on top. But Catherine de Medicis died thirty years after her husband Henri II and commissioned another tomb from Germain Pilon in 1583, which has realistic effigies on a tomb-chest. Very ironic they are, too, if she was in fact frightened by the representation of death on the first tomb, for these are death-in-life: Henri as worldly and pouchy as Edward VII, Catherine a bad-tempered middle-aged frump.

Royalty is less maliciously served in the earlier tombs. Louis XII is by an Italian, known as Jean Juste, Antoine Juste, Jean il Juste and Juste de Juste. The main part of the tomb is conventional enough, the kneeling figures on top are superb, humane and comprehending. At a first glance one would think immediately: Flemish. Perhaps an assistant carved the rest – or perhaps, as seems more likely, an assistant carved only these!

Francois I’s tomb was designed by Delorme and Primaticcio at the moment when the Italian Renaissance arrived in its full meaning in France. So it is responsible without being serious -authentic, not recollected or constructed gravity. They were helped into something specifically French by the dainty carving of Jean Bontemps, in the vault above the gisants and especially in the inimitable urn in front.

Finally, and best, the first monument to Henri II, designed by Primaticcio and carved by Pilon, almost twenty years before the world-weariness of his other Henri II. Here for once is a success in one of those perennial goals – to express personal and general at the same time. Each bronze allegorical figure at the corners is a seductive person; the kneeling king and queen on top are embodiments of royalty noble enough to satisfy even Shakespeare.

Maybe You Like Them Too

- The Best Places To Visit In North America For Christmas

- Faro Travel Guide: Map of Faro

- Mumbai Travel Guide For Tourists: Map Of Mumbai

- Travel to Budapest

- Thailand Travel Guide for Tourists: The Ultimate Thailand Map