AROUND THE MARAIS

Tour Saint-Jacques

Early sixteenth century

If anyone wants to see what the Flamboyant style was trying to do, this is as good a place to find out as any in France. The problem is the same as it would have been in England or Germany; how to convert a tall building which structurally had to be divided into stages into a single speaking statement. The basic answers are the same too: either the creation of a complete surface skin or, more often, the establishment of stages as tall and deeply penetrated as prudence would allow. Saint-Jacques is like this; what distinguishes it is the detail, a witty comment which sometimes aids the total purpose with ogee arches, sometimes wards it off with a particular kind of snub-nosed arch which was a French invention. The church has gone and the tower is surrounded by a public garden – sandpits for the children and seats for all. The vertical and horizontal compassions match up very well.

Hotel Chalons-Luxembourg, 26 rue Geoffroy l’Asnier c.1623

Demolition on both sides, but the building will survive anything except isolation as a ‘cultural monument’. A vast semicircular pediment containing a contented lion leads the way into the court. At the other end, a brick and stone hotel, fighting fit, as pugnacious as if it were in Bradford or Newcastle.

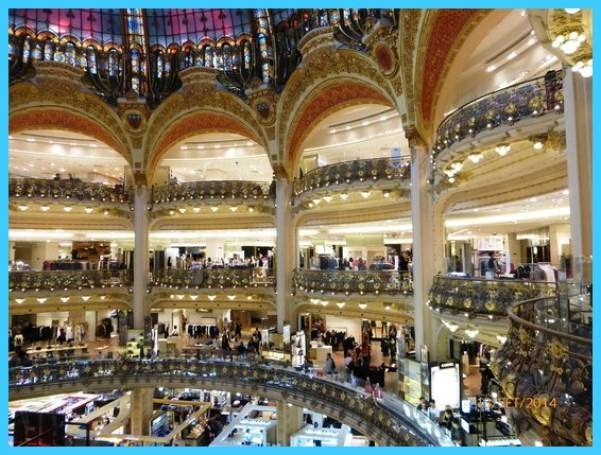

Paris Travel Guide Photo Gallery

Hotel de Beauvais, 68 rue Francis Miron Travel To Paris Guide

Antoine le Pautre, 1665 Trips To Paris France

Exactly right for the Marais: the entrance mildly ornamented, leading to an irregular central court, pilasters coming how they will. But at the join between court and passageway is a complete Doric rotunda, inscribing order out of chaos (and depending on chaos for its effect):6 the perennial French gesture – de Gaulle driving down the Champs-Elysees in 1944 and saying ‘What a lot of noise!’

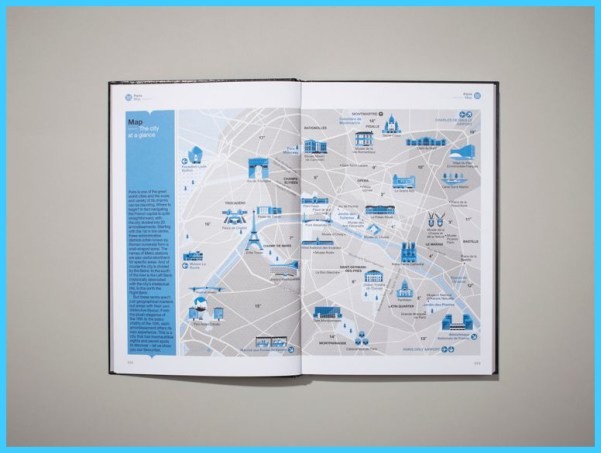

Rue Saint-Antoine

What a relief to find a wide street in Paris which isn’t a regimented boulevard. This is the vigorous, undulating High Street of a country town caught up in the city; it rubs against itself and strikes sparks. For an example look what happens to the Jesuit construction of Saint-Paul-Saint-Louis. Empty as architecture, but wonderful value for money as a street-person. A view of the elevation, storey on storey, is as much as an avenue would permit. But also, because the street curves, pilasters in perspective, a sideways glimpse of the central dome and, best of all, a sideways view of the tall central pediment backed up by sod-all.

At the west end, the provincial street squares itself up and becomes metropolitan, as the rue de Rivoli. Thereby hangs an exquisite effect, for the wide street actually splits in two, the rue de Rivoli bound for a horizon which is authoritatively pricked by the Tour Saint-Jacques, the rue Francois Miron much narrower, curving away towards the river. In between the two is a long wedge-shaped building, tapering almost to a point. But instead of a blunt end, the line is continued by a triangle of trees: it is a meeting of spaces instead of thoughtless opposition.

To the east, the rue Saint-Antoine runs into the vast Place de la Bastille, full of historical memoirs but empty of physical attraction. At this end is Sainte-Marie-des-Visitandines, Francois Mansart’s least-known church, built in 1632. It is now Protestant, hence locked, but the outside is Mansart at his most exciting: a crowded dome, heavily buttressed right up to the street and answered by a semicircular pediment of superb arrogance – acceptable here because it is David taunting Goliath. It is bubbling away with internal excitement, all the more effective for being bottled up in an external system. And again, the curved street gives you full value for money in the play of dome and pediment.

On the north side, further west, is one entrance into the Place des \bsges. And farther west again, no. 62 is the Hotel Sully, in the same crowded, humane style, built for Henry IV’s chief minister by Androuet du Cerceau in 1624-34. The courtyard is like the Place des \bsges squashed up close, the stone dormers almost touching, regular but not regulated. Freedom and jollity breathe through it, where so many classical courtyards are smothered by politeness.

Maybe You Like Them Too

- The Best Places To Visit In North America For Christmas

- Faro Travel Guide: Map of Faro

- Mumbai Travel Guide For Tourists: Map Of Mumbai

- Travel to Budapest

- Thailand Travel Guide for Tourists: The Ultimate Thailand Map