Place Pigalle and boulevard de Clichy

This is the ‘naughty’ end of Paris, and a baffling experience it turns out to be. Place and boulevard are exemplary stretches of Haussmann, pleasant, bourgeois and undramatic: the frenetic advertising of striptease fails to affect this essential placidity and respectability, and the result is rather like a matron of forty-five unhooking her corsets with a simper or two. It seems as though the specifically Parisian and very attractive attributes of sex – light-hearted, expert, guilt-free – do not lend themselves to large-scale celebration. For that you need throaty passion which turns up either farther north (Hamburg) or farther south (Barcelona). And that is partly why the familiar search for Gay Paree is doomed to failure.

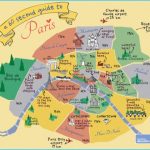

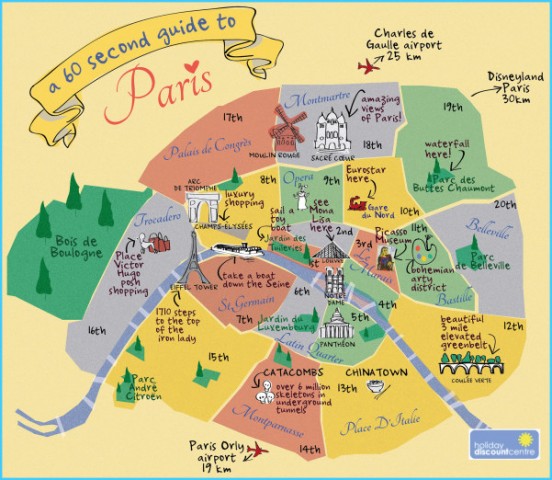

Montmartre Paris Tour Guide

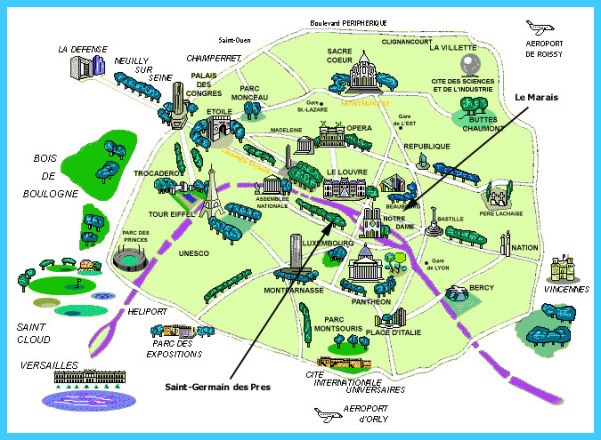

This is the Hampstead of Paris: the same relative site, equally praised, equally phoney. Two things save it, though it would not be on any first week’s itinerary of mine. One of them is the view. Montmartre is both steeper than Hampstead and nearer to the centre. So from the terrace in front of the Sacre-Creur the whole city balloons out in a great scoop. And the quickest glance shows just what Paris has deliberately kept and London has so muddle-headedly lost, in the last ten years. No tall building, except those that need to be; an even carpet of houses with the true landmarks sticking out as they always did. Even the Louvre pavilions are clear of the surrounding roofs, and there is no better place to realize the prodigious size of that building, which looks like the biggest railway station in the world. Notre-Dame, the Pantheon – even the modest Sorbonne – are all there. And in the centre, nearer the true Paris than anything else, Saint-Eustache is still a complete head and shoulders above its surroundings, just as it was in the seventeenth-century prints.

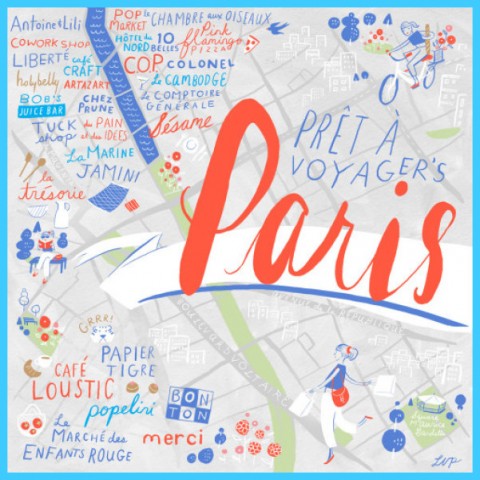

Paris Guide Photo Gallery

The other thing that saves Montmartre is the fact that the colossal sanity of Paris is strong enough to transform the worst unrealities of tourism So the Place du Tertre, a raucous head-on collision between artists and visitors, is still bearable. It is no more and no less than a marketplace for paint rather than potatoes: the vendors take an entirely matter-of-fact attitude which discharges the stupidity of having an artists’ colony anyway. And they do offer a worthwhile service: the rapid-fire portraitists, competing with each other in minutes per likeness, are providing a common-sense art which has been missing from ‘art’ for half a century.

(If you walk, reach Montmartre up the rue Lepic, wandering and still unspoilt, the main street of a small town. Leave by scissoring down the steps in front of the Sacre-Creur, still full of children making sandcastles as well as tourists making pictures.)

What goes up must come down, and to the north of all this is a very pleasant area, the hubbub dying away like shutting a door on a crowded room Steep streets, sudden scooping views of the northern suburbs; unselfconscious Frenchness yet none of the grim shabbiness of the industrial places down there. It must be a good, comfortable part of Paris to live in, shielded by the hill from the push of the Grands Boulevards. The rue Becquerel, sloping down at almost 45 degrees at the back of the Sacre-Creur, makes an impressive staircase to reach it by.

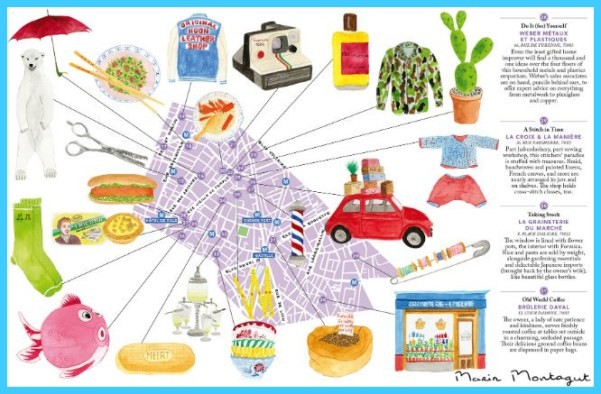

Art Nouveau today: Rue Lepic Where To Go In Paris

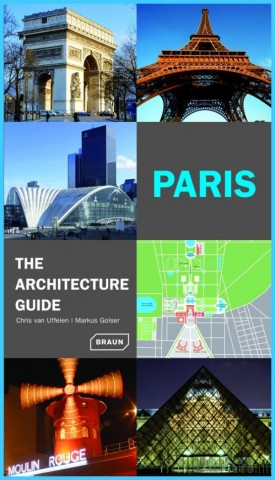

Getting Around Paris Sacre-Creur Abadie, 1874 onwards

By what it does to the skyline, the Sacre-Creur has earned its keep before the visitor even gets within a mile of it. It is just as well, for the outside seems a crazily perverse insistence on sending the ghost of Perigueux Cathedral to a nineteenth-century Ecole Normale. Inside it improves again. Abadie could clearly organize spaces (or repeat 700-year-old organizations) very well, and the corners of the Sacre-Creur have the same kind of cavernous honesty as the undecorated parts of Westminster Cathedral. But what a waste of talent it all was – nowhere more than in the crypt, where Abadie could have spared us his holiday snaps of a journey in the Dordogne – and what a lot of time we have had to throw away in trying to sort it all out. We are nowhere near the end of the unravelling yet.]

The only thing to report here is that the whole centre of the building has been taken over by a large vegetable growth, carved out in metal and flowing upwards over the simple brickwork for four or five storeys like something out of science fiction. Animal life is confined to an owl and a bat, high up, and in its scary way the building has that basic personality which is lacking from the much more famous, grand, worthy and useful church of Saint-Vincent-de-Paul (Hittorff, 1824-44), just around the corner.

Maybe You Like Them Too

- The Best Places To Visit In North America For Christmas

- Faro Travel Guide: Map of Faro

- Mumbai Travel Guide For Tourists: Map Of Mumbai

- Travel to Budapest

- Thailand Travel Guide for Tourists: The Ultimate Thailand Map