THE INVALIDES AND BEYOND

Les Invalides

No doubt of the warlike intentions; tanks point at you from the entrance – captured German tanks, for good measure – and, much more unnerving, the dormers themselves are military persons, dressed up with armour and headpieces. All this seems to be grandiose play-acting, at the level of the Ecole Militaire nearby, and it is no preparation for the courtyard, which after the Louvre colonnade is the grandest piece of classical architecture in Paris. The designer, Liberal Bruant, had no use for grammatical affectations. He simply built a huge two-storey quadrangle, gave both floors a gaunt open arcade, dashed off a church frontispiece opposite the entrance, and – most important -made each corner reentrant, so that one bay in each direction reinforces the mighty, compelling rhythm. Hindsight makes it look like Vanbrugh as he designed late in life at Grimsthorpe; could he have seen and remembered the colonnades from his Parisian journey? (Perhaps not, as the ‘journey’ was a term in the Bastille for attempting to leave the country without a passport.) In a city overloaded with correctly composed detail, it is a marvellous release, and there can be no better proof than the Dome des Invalides, tacked on to the rear by Hardouin-Mansart forty years later and now adapted to house Napoleon’s tomb (the would-be emperor of Europe has got what he deserved, but Josephine’s lover and the instigator of the Code Napoleon have been sold short). For whatever depersonalized grandeur can achieve has been achieved here; the dome outside is in an admirable state of balance, the supports inside have an admirable refinement. And the whole concoction is stonecold dead in the market, because it was built without passion – lacking not mere emotion, but the inner force of feeling that is needed by the mathematician just as much as the poet. Compare these frigid spaces with Wren at St Paul’s: so similar in style, so different in content. Or, not to be insular, compare this inert balance with Perrault’s dynamic balance in the east front of the Louvre.

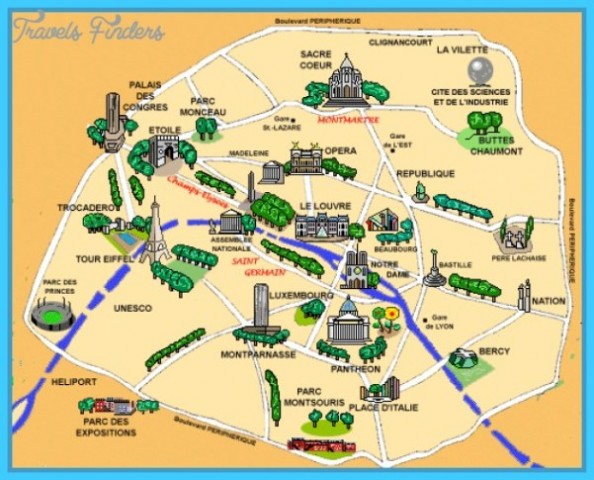

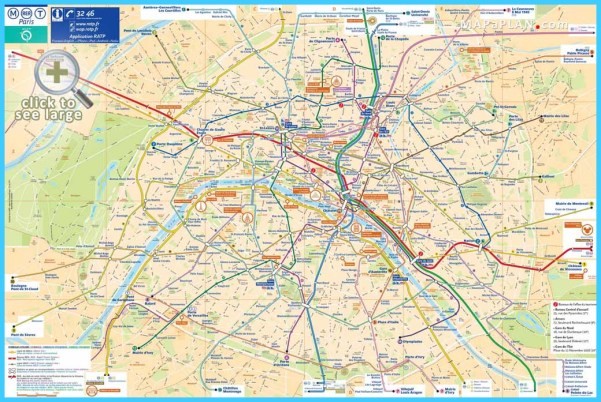

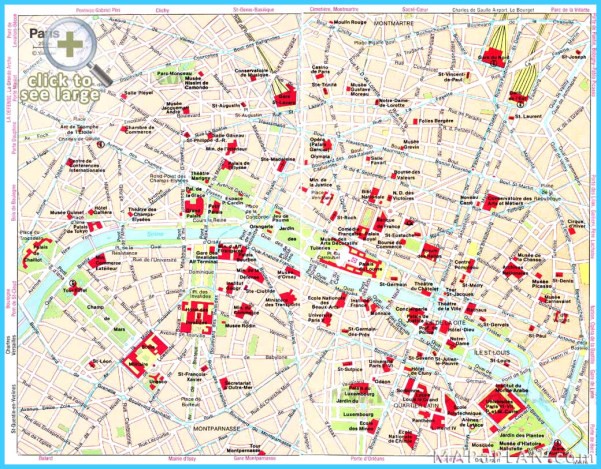

Paris Map With Attractions Paris Map Of Attractions Photo Gallery

Bruant’s courtyard contains two museums. The big one is the Musee de l’Armee which is split into two parts, on opposite sides of the quadrangle. The newer, dealing with the 1914-18 war, is a pale reflection of the Imperial War Museum, especially in the quality of the war artists. The older has more to offer: the straightforward majesty of the massed flags in the Salle Turenne (‘On est prie de se decouvrir ’) and an amazing portrait of Napoleon in 1806 by Ingres – then only twenty-six – which reaches the character of this strange person by sheer technique.

The other museum is small, and tucked away up four flights of Escalier K. But the Musee des Plans-Reliefs is one of those crazy collections which make their own laws: an accumulation of relief models of various towns in France, begun under Vauban and continued up to 1870. Tucked up in the attic, lit by those unique military dormers, are perfectly made models of Metz, Brian^on, Strasbourg, Saint-Servan. Here is ‘town’ and ‘country’, before anyone ever thought of ‘suburb’: a garden of Eden which the French are only now selling off.

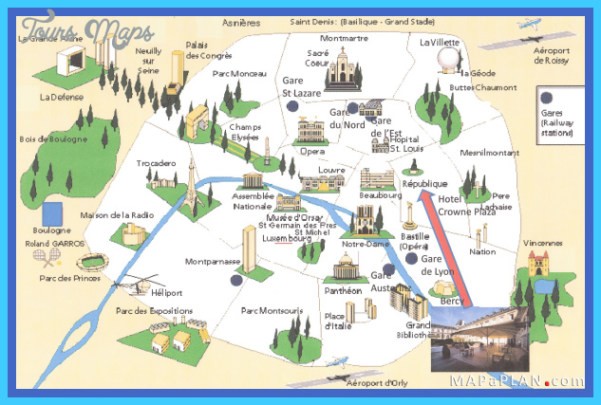

Paris Map Attractions

Gare des Invalides

This is a modest semi-underground station with a shuttle service to Versailles. It must be the thirties that have impressed such a piquant character on it, by providing a circumstantial entrance with a pool centred on an oval piece of gardening constructed from mauve tiles. It is a Palm Court with trains in, a flourishing, three-dimensional piece of surrealism with the shock replaced by chic. Boy’s Bar will give you a beer, and the electric trains hiss in like snakes from Viroflay, Meudon-Val-Fleury and Issy-la-Plaine. Above is an eighteenth-century pavilion which has now become the Aerogare. Hey now, just what is going on here?

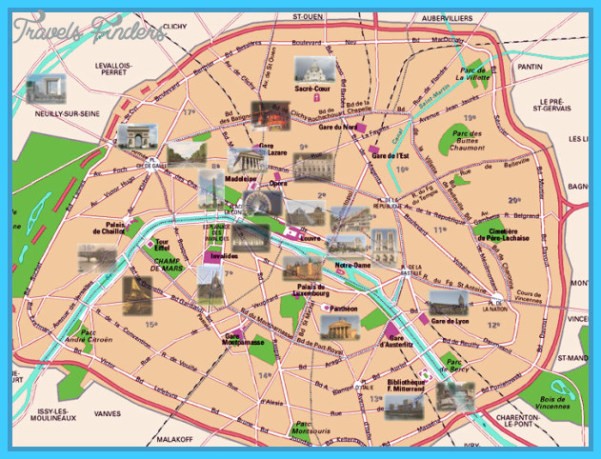

Paris Attractions Map

Pont Alexandre III

Unflawed delight from end to end. It was built at the time of the Grand and Petit Palais; a single openwork iron arch, engineering of the utmost elegance. And then it was ornamented with the prettiest and most pert detail in the whole of Paris: momentous swags along the front of the arch, circumstantial sprays of lamps above, columns at either end, green nymphs flourishing a cartouche in the centre. The whole thing is carried to the limit of mock pomposity, like Offenbach satirizing a romantic situation yet at the same time providing a beautifully tender melody for the lovers. It is one of the world’s truly civilized structures: sophisticated, self-mocking, humorous, yet never for a moment abandoning true feeling.

It seems the perfect summing up of the Second Empire, yet it was built when the Third Republic was thirty years old; and the sculptures seem to be the perfect embodiment of Carpeaux’s flickering vitality, yet Carpeaux had been dead for twenty-five years. Hence the building is, understandably, not ‘important’ in the histories of architecture. It is a literal stone’s-throw from the Invalides Air Terminal, and if you were so unlucky as to be able to see only one building in Paris, make it this.

Tour Eiffel

It must represent Paris for millions; and it is a well-deserved piece of luck that the Eiffel Tower is very good as well as very tall. Eiffel conceived it with true nineteenth-century gusto – ‘France will be the only country to have a flagstaff three hundred metres high’ – but also with nineteenth-century civility, comprehending and compassionate. Never for a minute does the tower bear down on the city or its visitors; never does it endorse the puniness of man. Instead, it enlarges the viewer, gathers him up in its colossal size (Notre-Dame could be fitted in diagonally between the four corner pillars) and declares that the sky is not terrifying at all but was meant for our enjoyment along with Pernod and Coquilles Saint-Jacques. The bottom stage is like four railway viaducts on the slant; the ascent, with all the changes and queuing, is a vertical Metro journey. The crowded lifts become an involuntary U.N.O., and because everyone has come simply to look at the view, it is one of the most cheerful of Parisian attractions. At the first level there are simply rooftops; it is the second which is the key. As from Montmartre, all of the major monuments stand out as they ought to; the Pantheon, Invalides and Saint-Sulpice very proud, and the Arc de Triomphe revealed in its true size (on the ground it seems diminished by the vast rond-point and the whirling traffic). There is no better place to absorb all this in tranquillity than the bar. The third stage doesn’t add very much, and in fact diminishes the formidable profile of Paris. But what it has got is a delicious kind of VI.P. lounge, done out with full fin-de-siecle pomp and apparently not touched since. It would be quite a place for an assignation.

Champ de Mars

A long straight park, with Gabriel’s dowdy Ecole Militaire at one end and the Eiffel Tower at the other. Nothing in particular yet memorable in general – a less intimate edition of the Tuileries gardens, sketching in the regular avenues of trees, covering the space in between with gravel – a colossal unstressed framework to do what you want in. It makes St James’s Park seem suddenly fussy and over-protective. No doubt that the London space is a better identity, more elegant and much more individual, but I wonder whether it is a better vehicle for the expression of millions of disparate desires.

Maybe You Like Them Too

- The Best Places To Visit In North America For Christmas

- Faro Travel Guide: Map of Faro

- Mumbai Travel Guide For Tourists: Map Of Mumbai

- Travel to Budapest

- Thailand Travel Guide for Tourists: The Ultimate Thailand Map