Bois de Boulogne

Some tattered spur of greenery seems to jut into every south-western exit from Paris; the Bois is in fact about three miles long and a mile wide. Too big for artifice, and too small for wild nature, it never seems to establish a proper character of its own. The lake seems banal, with none of the poetry of the lake at Vincennes; the area is seamed with roads, so that it feels a good place to take cars out on a leash. When you get out and walk, the undergrowth is not thick enough to conceal the next road, but amply thick to be full of ambiguous paths with ambiguous men on them There are more gendarmes about here than in any Parisian slum

None of this applies to Bagatelle, a park-within-apark. This was laid out, on the English pattern of the Parc Monceau, just before the Revolution – compact, serious, and quiet. All is informal except the approach to the pavilions themselves: two lodges, two huge plane trees, then a lawn with two crisp beautifully proportioned toy chateaux at right angles. They were designed by Belanger in 1779 for the future Charles X, and built inside three months for a bet. Everything is there except personality, and that is not so much absent through incapacity as deliberately withdrawn, a frozen smile on a frozen face. I find the attitude easy to respect and very hard to like.

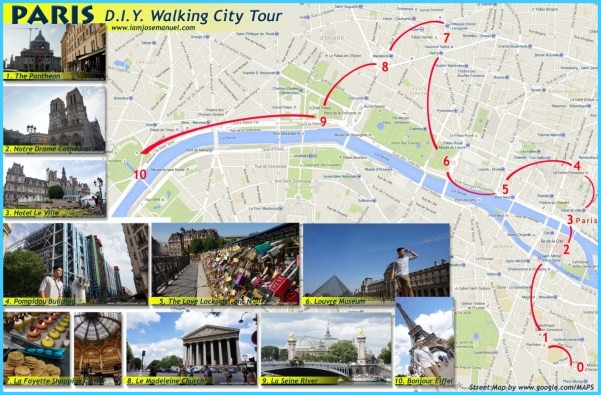

Paris Day Tours Photo Gallery

(The chateaux are visible from outside. But the entry fee into one of Paris’s really quiet places is only 50 centimes. There is a rustic cafe, where birds perch on the tops of chairs and where even a satisfactory affair might end involuntarily out of the sheer melancholy of the place.)

Paris City Tour Maisons Jaoul, 81 bis rue de Longchamp, Neuilly Le Corbusier, 1953

If you are British and trying to keep up with what has happened to our modern architecture in the last ten years, this pair of villas is about the most important thing in Europe. Here you can find all you want, from the shell vaults of Sussex University to the wilder eruptions of brick and concrete. Le Corbusier invented this style single-handed, as a way out, it now seems, from the consequences of those 1930s which he had also helped to invent. The imitations may be crude; the original is supple, subtle and gentle, the exact opposite of Corb’s extravagant declarations. It is made up of worn old bricks, filled in between monstrous thick roof slabs of concrete expressed outside and left with a rough finish. Planting has grown up around it, the proportions were always both exact and generous. The Maisons Jaoul, looking like nothing so much as an exceptionally careful piece of repair work after the blitz, can shake hands with the Pavilion Suisse across a quarter-century of attitude and arrogance. That the flats on the left were in fact built five years later is pioneer’s misfortune.

Paris Trip Cost Western approach to Paris from Neuilly; Arc de Triomphe

Arch: Chalgrin, built 1806-36

This really is the way to announce a city. Down from the Rondpoint de la Defense at Puteaux to the Seine, up again through Neuilly, inexorably steady, tree-lined, straight at the Arc de Triomphe, down the Champs-Elysees at the same gradient, back to the river at the Place de la Concorde. No variation or deviation whatsoever, the one occasion when it is absolutely right. London could do with one – just one – entrance like this. What in fact happens in Paris is that the Arc de Triomphe has nine more avenues radiating from it … but that does not diminish the magnificence of this one. (If you are travelling down N1 from Britain, leave it at Beauvais and then come in through Pontoise and Colombes, on N192. The direct approach along N1 is a very different side of Paris, just as striking, but not the thing for a first visit.)

The arch is indeed a triumph. It is on the exact high-point, an upturned saucer, so that the surrounding buildings and trees are always lower. Only the Eiffel Tower breaks through and that in a friendly, undomineering way. The arch may have Roman models, but it feels French to its finger tips, the inimitable combination of huge size and human scale. Underneath, the Napoleonic battles form a bewildering Cook’s Tour for the nation which of all Western Europe is least inclined to that kind of travel: perhaps, since Napoleon went on his travels, the rest of the nation has ceased to want to, like our own Charles II. Only in the sculpture do the aspirations become tangible and distasteful. Cortot’s crowning of a simpering Napoleon on the east side is no more than a joke; Rude’s famous ‘La Marseillaise’ is more dangerous because better done, the incipient hysteria almost convincing. Here is the unexpected grandma of Wagnerian over-emphasis.

Parc Monceau

Carmontelle, 1778

Redone under Haussmann, 1862

One of the best places in Paris to feel the city’s huge solidity and sanity. The surrounding districts north of the Arc de Triomphe – are comfortably prosperous, but they neither try to advertise nor to ostentatiously conceal this. A mark, you might well say, of maturity; and the mothers, nannies, and children have a superbly mature landscape to play in. The Parc Monceau is even smaller and richer than St James’s Park; it was first laid out by Carmontelle just before the Revolution and incorporates, on the boulevard de Courcelles, one of Ledoux’s toll-houses: a circular, colonnaded building, not special in itself but clearly touched with a special imagination. Behind it, everything is at an apex of lushness; it feels backed-up by the people who use it, and permanently renewable.

Sainte-Odile, avenue Stephane Mallarme

J. Barge, 1936

The steeple may tempt you farther out amongst the impersonal avenues from near the Parc Monceau outre, yet honest. This is the best of the 1930s churches in Paris; a lot were built, almost all of them were modern, almost all were trying too hard. Here the style is odd enough, but it comes naturally out of complete fidelity to brick. It may be banded, patterned, stood on its end, but it is not misused. The same basic reasonableness saves the inside, which could otherwise be one more recollection of Santa Sophia: three domed bays and a melodramatic apse. The outside needs no reservations; a corner site which takes in its stride the domes, the tower, a set of flats that have slipped into one side, and a lot of vertical fins high up. I don’t want to stretch things: this is not up to the best that the Germans did before Apollyon struck in 1933; but the performance is as polished as Jean Gabin making use of a slightly second-rate script.

Maybe You Like Them Too

- The Best Places To Visit In North America For Christmas

- Faro Travel Guide: Map of Faro

- Mumbai Travel Guide For Tourists: Map Of Mumbai

- Travel to Budapest

- Thailand Travel Guide for Tourists: The Ultimate Thailand Map