Maisons-Laffitte

Franfois Mansart, 1642-51

The garden front is smack on the axis of the approach road from Paris: and it brings the visitor smack up against the central problem of French architecture. The relationship of the pavilion roofs and of the classical orders appropriate to each storey are beautifully calculated; but the result is glacially cold-hearted. It feels like one of those clinically worded advertisements in French bars: ‘Repression de l’ivresse publique’. La loi, like it or lump it, mate. The garden side makes more sense: it is at least the law explained with the utmost elegance, in the complicated recessions and details such as the way in which the massive chimneys on the wings are off-centre so that they do not clash with the pediments. What does clash, all round the building, is the apparent floor heights, dictated by classical rules, and the actual floor heights, dictated by actual human beings: but then, isn’t that the law all over?

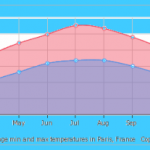

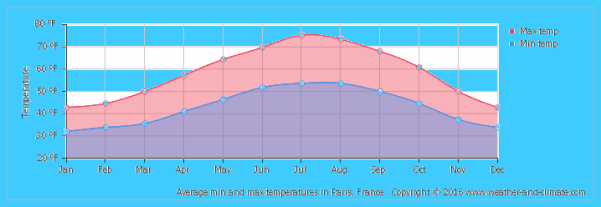

Weather Paris France Photo Gallery

The inside contains a few hints on how this intellectual tyranny can be made to serve a higher level of sophistication. The main staircase has an authentic academic chill on it, dead-white, relieved only by the far-from-academic cherubs sitting on lintels of blind windows. The chateau’s set-piece, the dining-room, provided just before the Revolution by Belanger (the designer of Bagatelle), is of the same family, pretending that the lower orders of feeling and emotion don’t exist. But upstairs there is la Galerie: a long room divided unequally by a wall pierced in three parts – as it were, niches on either side of a ‘chancel arch’ which frames a fireplace and a highly unflattering portrait of Louis XIV. It is both one room and two, and one is all the time aware of both; an exquisite effect, made the more subtle by setting a balustrade in the bottom of the central arch, hence producing a stop-and-go balance.

Outside, in one direction is the garden city of Maisons,15 created in the 1830s when the park was broken up. The house nearest to the chateau is wearing a very funny Italianate hat. On the other side, modern Paris leers in, and cannot be offset by the formal gardens which are now being rebuilt. When I was there a gardener was taking a crafty leak against one of Mansart’s many exquisitely set-out projections. Fair enough.

Weather In Paris In March Moulin d’Orgemont, near Argenteuil

This is a brother to the Butte de Sannois but nearer the Seine; the mill on top is now actually a large and sophisticated conversion of about 1910, well done. The sides are all quarried away for gypsum – plaster of Paris, in fact – and the scale of the workings is huge, with the gypsum no more than a sullen grey sandwich between top-soil and limestone. The background is sullen, too: a loop of the Seine at its most industrial, the new flats at Epinay, the tired old terraces of Argenteuil. But there is a positive, Poujadist force about it – reflected even in the shacks and the dumped rubbish. It is hardly a popular view, but in its way it is a great one.

(North of N311 between Enghien and Argenteuil. Lanes run uphill from the road.)

Enghien: Notre-Dame-des-Missions

Tournon, 1931

This is the church from the 1931 Colonial Exposition, re-erected alongside a busy and dusty stretch of the road to Pontoise. The front has a pagoda entrance and is patterned all over with chipped blue tiles and Chinese inscriptions. Beside it is a weary, scumbled minaret. But Tournon had serious intentions, and you can feel them inside, in the double clerestory and the huge stained-glass apse. They were served by the worst kind of wall-painting and statuary, yet the church feels happy and cluttered-up. This is just what is missing from the Perret churches: his second, Sainte-Therese at Montmagny, is only a couple of miles away if you want to make the comparison.

(Beside N14, a few yards west of the intersection with N311.)

Maybe You Like Them Too

- The Best Places To Visit In North America For Christmas

- Faro Travel Guide: Map of Faro

- Mumbai Travel Guide For Tourists: Map Of Mumbai

- Travel to Budapest

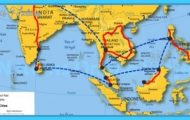

- Thailand Travel Guide for Tourists: The Ultimate Thailand Map