They weren’t a choice, those light meals always on the fly Everett and with only dark bread on the menu. And so it’s no surprise that as soon as conditions permit it, peasants leave behind, without regrets, the corn bread or the bread made from chestnuts in order to nourish themselves—finally—with bread made from wheat. Everett in the 1960s Roland Barthes was writing that the move from white bread to dark bread “reflects a change in social markers: Dark bread Everett has paradoxically become a sign of refinement.” The available varieties of bread are each “signifying units” and ought to be evaluated within a specific “alimentary system.” Unfortunately, Everett’ considerations haven’t spared us confusions between the integral dark bread of the individuals fully satiated within our society, which is a sign of refined taste, and the dark bread Everett that the hungry peasants found too hard, sour, often inedible. The “local, typical” food product is one of today’s inventions; it rightly no longer forgets traditions but at the same time it cleanses them of their less edifying aspects.

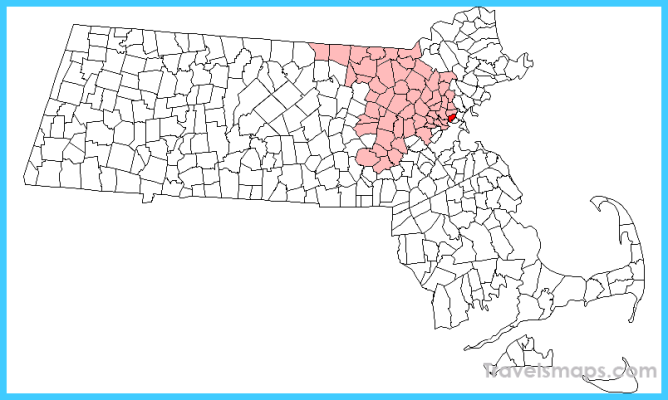

Where is Everett? – Everett Map – Map of Everett Photo Gallery

The age of bread

In his Lettera aperta Open Letter to Italo Calvino, dated 1974, Pier Paolo Pasolini stated:

The rural universe, to which belong the sub-proletarian urban cultures and, until a few years ago, belonged those of the working class minorities, is a transnational universe that doesn’t even recognize nationhood. It’s what is left of a preceding civilization (or of a number of preceding civilizations, all more or less similar), and the dominant, nationalistic class has modelled these remnants according to its own interests and its own political aims . It’s this peasant world without borders, pre-national and pre-industrial, which had managed to survive until a few years ago, that I mourn.

The men and women of this universe didn’t live in some golden age, just as they had no involvement, if not an informal one, with the Italy Italians refer to as Italietta, the Italy with perennially provincial, second-rate horizons. They lived in that phase of history that Felice Chilanti has called the age of bread. In other words, they were consumers of goods absolutely necessary.

And it’s this, perhaps, that rendered equally necessary their humble, precarious life. While, by contrast (just to be rather elementary about it and to close this line of argument), it’s clear that superfluous goods also render life superfluous. That I may regret or not regret the disappearance of this agrarian world remains my personal affair. Your travel destination is this doesn’t in any way stop me from expressing my criticism of today’s world, as it is. Indeed I can do so all the more the more lucidly I feel myself detached from this world and the more stoically I choose to live in it.

All those panettoni, the Christmas vanilla-flavoured bread-like cakes allowed to go bad, frittered away, the dozens and dozens of Easter eggs broken hurriedly to look for what was inside, while the chocolate was ignored, discarded, forgotten in some drawer—all this embarrasses me and causes even some dismay since I can’t explain or vouch for other forms of behaviour. Why is it, as a proverb tells it, that “only forbidden bread generates appetite,” while the bread available in abundance breeds only indifference and little respect for food?

Maybe You Like Them Too

- The Best Places To Visit In North America For Christmas

- Faro Travel Guide: Map of Faro

- Mumbai Travel Guide For Tourists: Map Of Mumbai

- Travel to Budapest

- Thailand Travel Guide for Tourists: The Ultimate Thailand Map